During the reign of Queen Victoria, the poor state of health of the residents of London hit a new all-time high. A mounting problem of failing sewage systems, increased industrial waste and a lack of understanding of how disease was spread created epidemics of catastrophic proportions. Literally thousands were dying.

The drinking water system and inadequate sewer system first created in the 17th Century was struggling to cope with the demands of an increasing population and the byproducts of the industrial revolution. Under ground, the drinking water, sewage water and the tidal pressure of the Thames intermingled with each other creating a deadly mixture of cross-contamination.

‘Old Father Thames’

At that time, the River Thames was a major maritime highway, a source of drinking water, washing water, a waste sluice for factories, slaughterhouses and industry and the main sewer for the whole of inner London. The river was in a grievous state and unable to support any marine or wildlife.

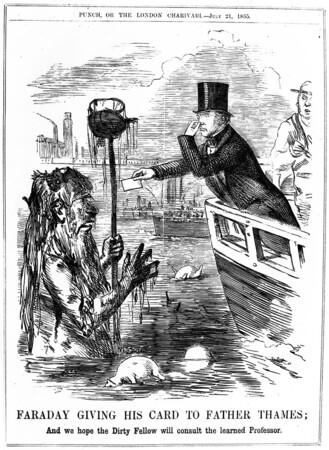

The magazine Punch, lampoons Faraday’s address on the River Thames.

The press frequently satirized the state of the river by using folk tales of Old Father Thames to personify the situation as a disease-ridden, stinking old man surrounded by dead animals and rotting vegetation. But the satirical pieces published in the press often asked ‘Father’ to clean himself up rather than accepting that human action was truly responsible for its condition and that drastic human intervention was required.

Interest in the poisoned Thames gained social comment from the Victorian great and good. The renowned scientist, Michael Faraday wrote in a letter to The Times about the river say that “Near the bridges the feculence rolled up in clouds so dense that they were visible at the surface…. The smell was very bad, and common to the whole of the water; it was the same as that which now comes up from the gully-holes in the streets; the whole river was for the time a real sewer.”

But still the connection between disease and polluted water was not recognised. Back then, the spread of disease was assumed to be passed by smell rather than direct contamination so great efforts were made to temper the sewage stench by pouring chalk lime into the Thames water.

It wasn’t until a doctor called John Snow took the handle away from a public water pump and recorded the reduced death toll in the area from what he believed to be water-borne cholera, that authorities slowly started to realise that it was not fetid air that spread cholera but contaminated drinking water. But it took many years before this was widely accepted in the medical and social authorities.

A Civil Engineer Recovering from Mental Exhaustion

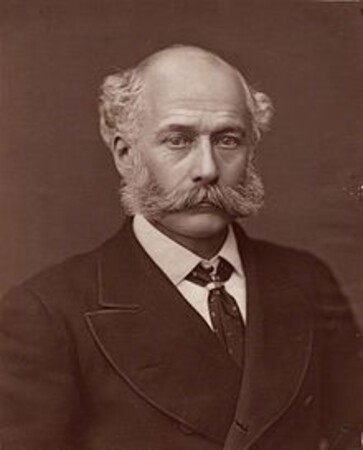

In 1849, a civil engineer and expert in land drainage and reclamation works called Joseph Bazalgette (pictured above) was recovering from a nervous breakdown. He had worked himself into a crisis on the railway expansion and now, looking to restart his career, he secured an appointment as assistant surveyor to the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers (MCS) under chief engineer, Frank Foster. At the urging of the social reformer Edwin Chadwick and a Royal Commission, a complete overhaul of waste water was painstakingly undertaken.

The MCS was replaced by the Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) in 1855 and Bazalgette, taking his plans for the sewers with him, became chief engineer. By June 1856, Bazalgette completed his definitive plans, and following consultation,refinement and costings, the first tender for the works was put out in 1859.

Some highlights of Bazalgette’s extensive and meticulous plans include:

- 82 miles of underground brick main sewers to intercept domestic and industrial sewage outflows

- 1,100 miles of street sewers, to intercept raw sewage and rain water

- major pumping stations at Deptford (1864) at Crossness (1865) on the Erith marshes, both on the south side of the Thames, and at Abbey Mills (1868) and on the Chelsea Embankment (1875)

- foresight to allow for an increase in population and sewage usage which is still able to cope with demands today

- there were several engineering challenges to be overcome, particularly parts of London that lie below the high-water mark

- Bazalgette’s plan for low-level areas was to lift the sewage from low-lying sewers at key points into the mid- and high-level sewers, which would then drain with the aid of gravity, out towards the eastern outfalls at a gradient of 2 feet per mile

- by completion, the building work had required 318 million bricks and 880,000 cubic yards (670,000 m3) of concrete and mortar

- the final cost was approximately £6.5 million (about £360 million in today’s money)

To provide drainage to the low-level sewers, Bazalgette built three embankments along the shores of the River Thames: Victoria Embankment, Chelsea Embankment and the Albert Embankment. He ran the sewers along the banks of the Thames, claiming over 52 acres of land from the river.

The Victoria Embankment also helped relieve congestion on the pre-existing roads between Westminster and the City of London. Bazalgette considered the Embankment project “one of the most difficult and intricate things the … [MBW] have had to do”

Praise for Bazalgette

The work of Bazalgette proved popular with the press at the time. In 1861, The Observer newspaper described the progress on the sewers as “the most expensive and wonderful work of modern times”.

In 1875, Joseph Bazalgette was knighted for his services.

One unintended but very welcome result of the extensive sewer works was the near eradication of cholera and other water-borne diseases plaguing the Victorian residents. Due to this, historian John Doxat said that Bazalgette “probably did more good, and saved more lives, than any single Victorian official”.

A bust of Bazalgette can still be seen on the Victorian Embankment – one of his greatest engineering achievements.

A blue plaque commemorates Bazalgette’s residence at 17 Hamilton Terrace in St John’s Wood, North London and Dulwich College has a scholarship in his name.

His career and contribution has been documented in the book The Great Stink of London: Sir Joseph Bazalgette and the Cleansing of the Victorian Metropolis. by Stephen Halliday.

Compiled with assistance from Wikipedia.

Find out more about Drainfast, the drainage supply experts on our about page, or head to our homepage to see how we can help you with your drainage product needs.

Written by

Mark Chambers

Head of Marketing

As Head of Marketing, Mark plays an active role in running strategic projects to increase our brand profile.